SOUND INTO IMAGE:

The Collaboration between David Tudor and Sophia Ogielska

The Collaboration between David Tudor and Sophia Ogielska

by Billy Klüver and Julie Martin

All great artists master the traditional styles and forms of their art. David Tudor was a legendary performer of classical organ and piano music and toured Europe extensively during the 1940s and early 1950s. Driving with him from Paris to Stockholm in 1974, we stopped at every major cathedral on the way and he described in detail the qualities and complexities of their organs. This mastery is reflected in the rigor and energy of Tudor’s approach to interpreting the work of contemporary composers and in creating and performing his own work over the last 30 years.

When Robert Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver were assembling artist friends to work with engineers on performances for 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineeringin 1966, it was natural to ask Tudor to participate. In his piece, Bandoneon!, the sounds from the bandoneon were picked up by contact microphones, processed and modified by electronic equipment — designed and operated by engineers Bob Kieronski and Fred Waldhauer — and then switched between speakers and acoustical modulators placed around the Armory. The sound was also used to control the stage lights around the Armory. For Bandoneon! Lowell Cross had designed a system to modify images from three television projectors. As the performance progressed, Tudor played the entire Armory, with its six-second reverberation time, with sound and light.

Experiments in Art and Technology was founded during 9 Evenings. From the beginning, Tudor’s input has been crucial in formulating the directions and programs of EAT. At board meetings his often disarmingly simple suggestions would set moral and practical baselines for approaches that would quickly resolve the question at hand.

Tudor was one of the four artists who initiated the E.A.T. project to design and program the Pepsi-Cola Pavilion at Expo ‘70 in Osaka, Japan. Together with Fred Waldhauer and Gordon Mumma, Tudor undertook the design and programming of the sound system for the Pavilion. The interior space of the Pavilion consisted of a 90 ft. diameter spherical mirror; and thirty seven speakers were arranged in a rhombic grid on the surface of the dome behind the mirror. Sound could be moved at varying speeds across the dome and in circles around the dome, shifted abruptly from any one speaker to any other speaker. Tudor made nine pieces for the dome-shaped space. Three of them, Pepscillator, Pepsibird, and Anima Pepsi were recorded by Sony at the Pavilion.

In the early 1970s Tudor conceived another E.A.T. project, Island Eye Island Ear, a concert to be held on an island. Tudor would place parabolic antennas in configurations around the island to create sound beams and sound reflections. The inputs would be sounds of the island recorded over the course of one year. We asked Fujiko Nakaya to contribute Cloud sculptures and Jacqueline Matisse Monnier to make long-tailed kite works.

In 1974, we went with Tudor to Sweden to do tests on Knavelskär, an island in the archipelago outside Stockholm. Tudor fed sound into the antennas, either facing each other or facing rocky Cliffs, and the resulting sound was glorious. We flew kites Monnier had given us from the high cliffs over the sea; and Nakaya generated voluptuous fog using a portable generator, bottles of compressed air, and sea water.

Tudor’s process of constructing his musical performances is similar to the philosophy behind the development of a system for 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering to control the varied functions the ten artists required for their very different pieces. [1]

The defining characteristic of Tudor’s music is that the source of the sounds is the behavior of the electronic circuits themselves: oscillations, amplifications, modulations, frequency filtering, attenuation, switching. By interconnecting discrete units that perform these various functions, Tudor builds up his musical instrument.

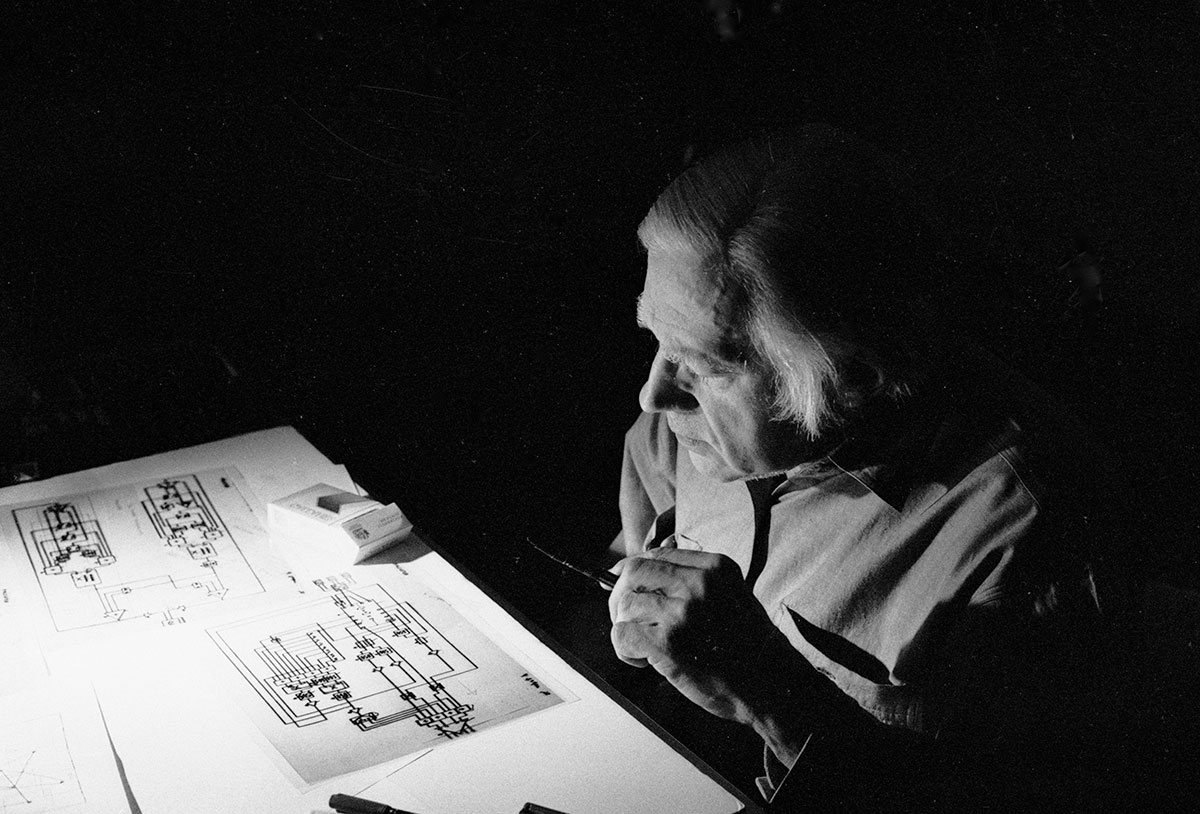

Tudor’s “scores” consist of what looks like block diagrams of circuit design, but he modifies and adds to the commonly used symbols ‐ e.g. for amplifier or controls, etc . ‐ in his own fashion, but of course carefully explaining what he means. A typical block diagram would show: indications of the number of channel inputs; “bypass or on off controls”; modifications of the input sound: which could consist of AM modulation, FM modulation, or filters all with “vary controls”, sound modifier outputs, gain controls, clocks, and if available pre‐programmed controls. The output from all of this is moved among as many speakers as Tudor could lay his hands on.

Sometimes Tudor used color in his diagram, such as in Pepscillator, where the colors served as added dimensions of information about the functioning of the system: red for activity and green for critical adjustment, blue for connections, with yellow boxes surrounding certain units.

For a typical Tudor work the equipment itself ‑ potentiometers, amplifiers, filters, etc. ‐ was housed in standard aluminum boxes or built on bread boards, all temporarily patched together to achieve the particular function Tudor required. The functions and operation of all his equipment was well understood and catalogued in Tudor’s mind. Before each performance, he worked with prefabricated cables and connected the various electronic elements into what became one single instrument for playing. The instrument had been fabricated in front of our eyes and Tudor’s overflowing table with its boxes, cables, batteries, and tape recorders was with its intricacy a fascinating and wonderful sight to see.

To build up his performance works Tudor relied heavily on buying equipment from mail order catalogues, such as Federated or Edmund Scientific, and on his good friends in engineering, like Fred Waldhauer, Carson Jeffries, Lowell Cross (who is also a musician) and Forrest Warthman.

A sound generating system like Tudor’s has two unique characteristics: it can be entered or triggered at any point; and the sequence of activating the components is dependent on the real-time actions of the performer. Because of inherent instabilities in the circuits, Tudor’s performance of a work could never be replicated to, say, the degree a piece of classical music could. Tudor’s music is all real‐time performance by himself. As he has said:

“The performance is like performing the possibilities which are in front of you. And so what’s in front of you becomes the composition. And then going from that, you choose among the possibilities what you want to appear, and then it’s the task to make those things appear. So if they don’t appear at one time, then you try another time. The initial choice is: how much variety you wish there to be. So you try to make it happen or you try to arrange for it to happen. That’s what I do.” [2]

Tudor was concerned with the problem of formulating how he operated but knew of no notation system that could adequately express the situations developing during the performance of his work. In 1994 the Merce Cunningham Company had revived Sounddance, for which Tudor played Toneburst, and the company wanted to make it a permanent part of the repertory. Toneburst is a physically demanding piece, and as his fellow musician John D.S. Adams told us that in performing it , “David used every musical bone in his body.” Each performance left him exhausted and close to tears, but exhilarated. Tudor was thinking of ways to develop a “robot” that could “execute” some of the functions during a performance. He was always fascinated by mechanical motion and as John Adams recalls, he was thinking of a construction that would execute physical movements.

We introduced Tudor to our neighbors Sophia Ogielska, an artist and Andy Ogielski, a scientist from Bell Laboratories, thinking that some of the technology that Andy had developed in his laboratory ‐ in particular work with neural network chips ‑ would interest Tudor.[3] However, when Tudor visited them in the spring of 1994, and looked at Sophia Ogielska’s paintings, he responded to the way she organized visual information.

In her paintings Ogielska was interested in “visual synthesis of complex structures…following the observation that the appeal of complexity arises neither from predetermined organization, nor from complete randomness: complex structures emerge from interactions of their parts.” They were many “fragments”, creating images of structured disorder of desert stone patterns, fractured earth, and other natural subjects, in a process she describes:

”The fragments are painted first. They are small, independent works each with its own complexity and logic. Then I build a bigger and more complex space by fitting, combining and overlapping the earlier painted fragments. In this process of arranging and rearranging, higher order structures emerge, structures which are unpredictable but not random.”

In the complex image surfaces she creates, there is no focal point, no horizon, no perspective; the eye is free to move from detail to the whole, or from one detail to the next. As she says, “structure and a certain natural order emerge from visual associations imposed by the mind.”

Tudor suggested that he and Ogielska develop a project together that combined sound and images. They immediately decided to concentrate on one piece Untitled, 1972 and its performance as Toneburst. As Tudor explained to Ogielska “Its output configuration has a structure for 18 minutes.” During the first 14 minutes he introduces all the elements he wants to introduce and, “after 14 minutes a pulse is introduced which intensifies in volume and is drawing the piece to the end. The final 4 minutes increase in volume and activity.” Eighteen minutes was the minimum time he needed to present the piece, but a concert version could extend for any length of time. Tudor once played it in Europe for 6 hours; and he joked with Sophia Ogielska that he would love to “play it until he dropped.”

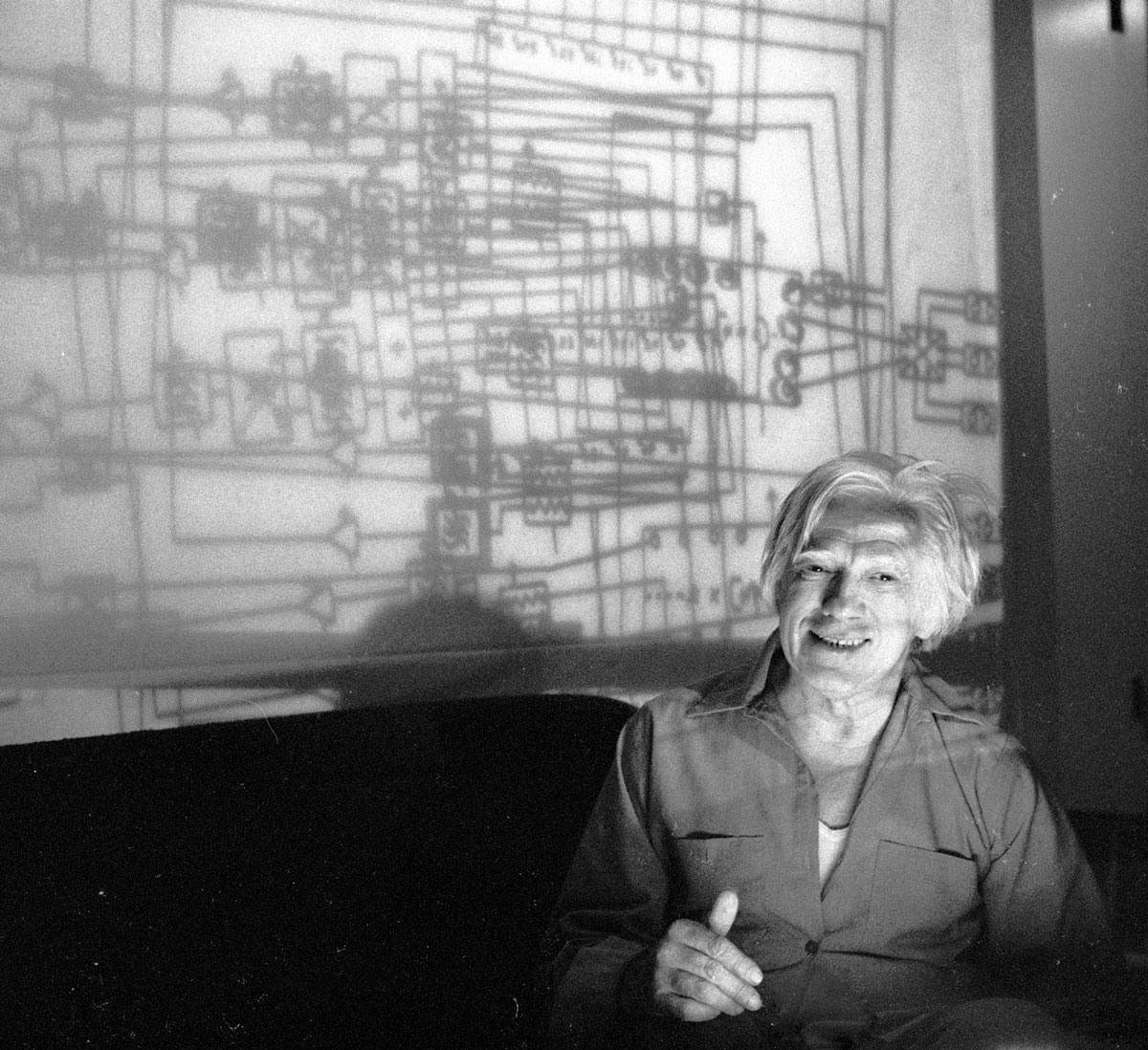

Their work developed with many meetings and discussions over several months and many trials of how to connect sound with image. The project took its present form when Ogielska copied Tudor’s circuit diagrams Untitled and Toneburst onto transparencies and brought an overhead projector to Tudor’s where they projected the diagrams on the wall of the room. She watched as Tudor silently “played” the work in different “performances”, moving his hand from component to component, trying out different versions. Over time, they realized that though there were many more components in the original block diagram, Tudor only activated 23 of them. They focused on visual representations of these 23 components.

One of the first decisions they made was to use bright primary colors and Tudor began to identify and designate the active components on the diagram. Ogielska’s notes in February 1995 record Tudor’s choice of colors for the components: “Blue = longtime operation. Anything that is controlled by a potentiometer is a long time operation. Red = switches. Anything that is controlled by a switch is a short-time operation. Green = frequency-selective components. Further differentiation will be confusing.”

Since Tudor operates on a number of electronic components at once during his performance, Ogielska and Tudor decided to work on transparent media to represent simultaneous multiple operations. The use of multiple layers and color shadows became a natural element of their work.

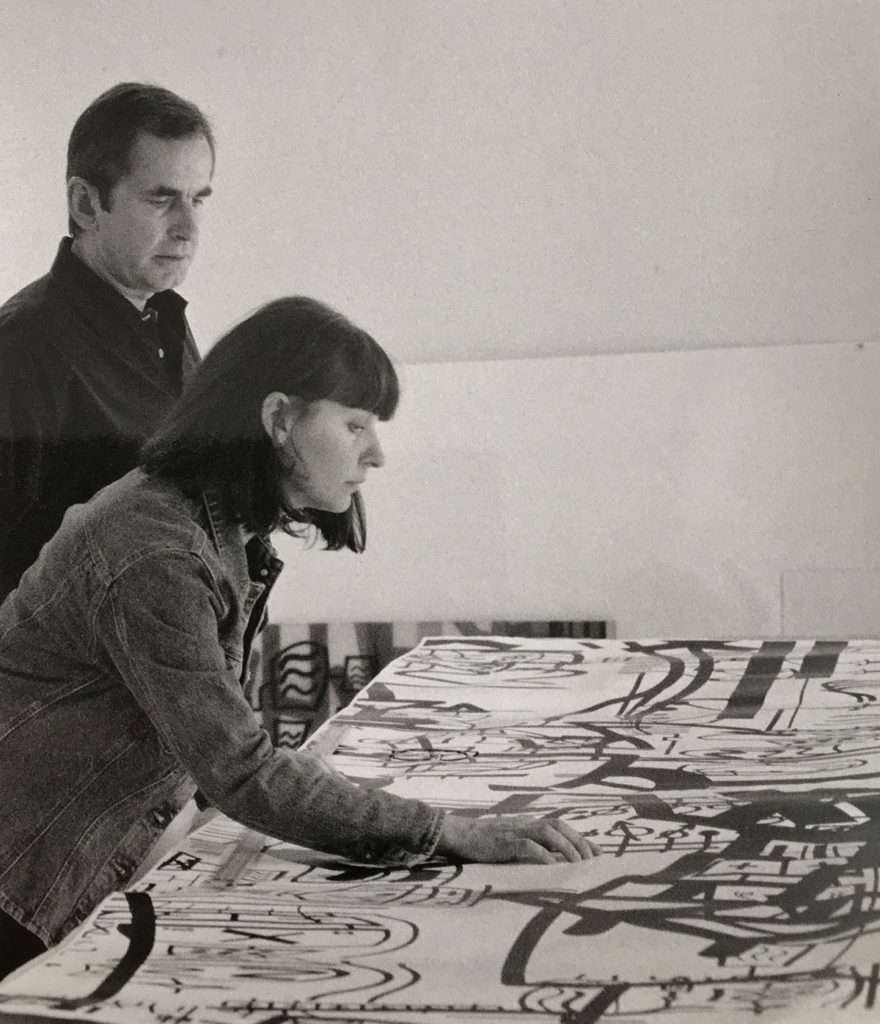

Andy Ogielski at the time was writing an interactive graphics program using spline functions, where a transformation brings a two‐dimensional image onto a surface in three‐dimensions. With the program you are then able to manipulate or shape this image in three‐dimensional space ‐ enlarging, elongating in any direction, folding in on itself, etc. The manipulated image is finally projected and drawn on a two-dimensional surface. To test his program Andy Ogielski input one of Tudor’s circuit diagrams and performed some simple manipulations on them. When Sophia Ogielska showed the results to David Tudor, he loved the idea of working with the program – conceptually and visually. They began to work together to evolve new shapes for each of the the 23 active components. Sophia Ogielska learned the program and would produce images to show Tudor, or they would sit together at the computer and manipulate the shapes on the screen.

David Tudor and Sophia Ogielska demanded that the surfaces and the morphology of the shapes became more complex, and Andy Ogielski was required to expand his program several times to keep up with them. They would agree on the final “shape” of each component, Sophia Ogielska remembers, when “I would say ‘That looks good,’ and David would say, ‘That sounds good.’ Three different colored groups of graphic shapes describing the active elements in the performance emerged: 12 blue images of potentiometers for controlling signal distribution; 6 red images of input output switching; 5 green images for frequency control and selection and phase shift; yellow lines represent the constant input from tape recorders. Delighted with 23 lively, colorful, almost cartoon-like graphic shapes, which they sometimes called ideograms, Tudor declared, “Now I have a language.”

They then assembled the 23 graphic shapes into anew block diagram, leaving out some wires connecting the components. This new diagram became the image that Sophia Ogielska and Tudor repeated in assembling the large Maps. Sitting at the computer, they essentially used the same method of composition that Sophia Ogielska had used in her earlier work, and began to add one image of new diagram to another, stretching some and shrinking others, fitting them together as Sophia Ogielska has said, “like a puzzle.” This continued until they had a built up Map that satisfied both of them.

After she and Tudor created five of the Maps, Tudor became blind following a series of strokes. This did not diminish his interest and involvement in the project. Sophia Ogielska would describe what she was doing and together they would decide on the evolution of the project. He joked, Ogielska remembers, “Now that I can’t see, I’m a visual artist.”

They wanted the Maps to be as large as possible, and Toneburst Map 4 measures 96 x 96 inches. The dimensions of the Maps are variable and Toneburst Map 1 Version 2, in fact, is divided into three sections, each of measures 85.5” x 29.5”.

Color was introduced into the Maps in two ways. For Toneburst Map 1 Version 2 and Toneburst Map 4, two separate works, free hanging mobiles titled ldeogram Clusters , each made of 5 or 6 strips of clear acrylic 16” and 14″ wide and 96″ long carrying color images of the graphic shapes, will hang in front of panels containing the black Maps and cast color shadows on them. In the other three Maps, color images of the graphic shapes were superimposed on the basic black images in the computer and are physically part of the large panels created from the computer files of these maps. Taking small fragments from these three Maps, Sophia Ogielska has made a variety of smaller colorful works titled Toneburst Fragments, that are made up of five or seven layers acrylic, each layer carrying a full or partial color image of one of the different colored graphic shapes of the components.

In the realization of these works, a computer-controlled film cutting device cut the shapes in vinyl film. The cut film, either black or painted by Sophia Ogielska with translucent colors, was then laid on clear acrylic sheets.

Tudor’s original block diagrams describe the instrument he uses to perform Untitled and Toneburst. The Maps and Fragments that Tudor and Sophia Ogielska made can be seen as a description of the performance and the possibilities inherent in multiple performances of the work. Tudor felt that they had created a language through which the performance of his work could be described. The Maps can be read as scores, which can be entered at any point and traversed in any direction, producing, in effect, oneperformance or many performances. The collaboration between Sophia Ogielska, Andy Ogielski, and David Tudor has produced bright, energetic works that not only act as a visual equivalent of his music, but are the visual expression of Tudor’s commitment to choice and responsibility that have guided his work and his life.

NOTES:

1 Developed by Fred Waldhauer, Robbie Robinson, Herb Schneider and others engineers with strong input from Tudor, the system consisted of small battery‐driven preamplifiers, power amplifiers that could deliver 10 watts, and 80 db differential amplifiers, tone control units, FM transmitters, signal encoders and decoders, and power relays, that could be arranged in different configuration each artist’s piece.

2 The quotes by David Tudor are from notes taken by Sophia Ogielska during their work together and from an annotated bibliography compiled byJohn Holzapfel, who has written extensively on Tudor’s early performance work. “Composer Inside Electronics: David Tudor im Gesprach mit David Fullemann,“ MusikTexte , No. 15, July 1986, pp. 11‐17.

3 Ogielski is currently a director in the Information Sciences Research Laboratory at Bell Communications Research

©1996 by Billy Klüver and Julie Martin